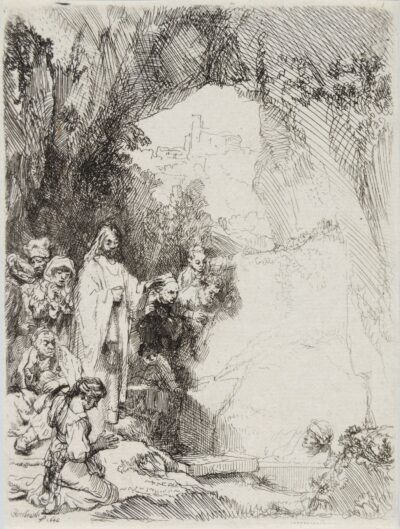

Abraham Casting Out Hagar and Ishmael

Rembrandt Van Rijn

Abraham Casting Out Hagar and Ishmael

etching & drypoint

1637

An original Rembrandt Van Rijn etching & drypoint print.

1637

Original etching with touches of drypoint printed in black ink on laid paper.

Signed and dated in the plate upper right Rembrandt f 1637.

A superb 17th century/lifetime impression of Bartsch, Hind, Biorklund/Barnard, Usticke and New Hollstein’s only state of this delicate etching, in which the distant buildings are still printing fine and clear.

Catalog: Bartsch 30; Hind 149; Biorklund-Barnard 37-A; Usticke 30; New Hollstein 166.

Image Size: 5 x 3 ¾ inches

Sheet Size: 5 x 3 ¾ inches

Abraham’s dismissal of his concubine, the Egyptian servant-woman Hagar, and her son Ishmael, is a complex domestic drama. Sarah, Abraham’s wife, had given her maidservant Hagar to Abraham to warm his bed. But when the younger woman bore Abraham a son, Ishmael, things became more complicated. Later, when through God’s intervention a son, Isaac, was born to the elderly couple (Sarah was ninety and Abraham was ninety-nine), Sarah became concerned for Isaac’s inheritance and asked Abraham to send Hagar and Ishmael away. Abraham was reluctant, but God reassured him, promising that Ishmael would become the father of a great nation (Genesis 21:13-21). Ishmael, who was to become a skilled archer and fierce warrior, is considered to be the founding father of the Arab (Muslim) people.

The elaborate chain of human interaction in Rembrandt’s small 1637 etching matches the complexity of the story. There is a dramatic arc of expression and gesture that begins at the left with the figure of the triumphantly grinning Sarah looking on with satisfaction from the window; continues through the small Isaac peeping out of the door with a sly, gloating expression; descends the steps with the faintly smiling family dog; passes through the emotionally divided figure of Abraham; and ends with the faceless figures of Hagar and Ishmael, already moving away. The weeping Hagar, water flask at her side and bundle under her arm, has her face buried in her kerchief, while the valiant small figure of Ishmael seems already to be marching determinedly toward his future. As with a number of Rembrandt’s biblical narratives, this one takes place on the symbolic threshold of a home. Sarah and Isaac are securely in position within the house while the pivotal figure of Abraham literally has one foot inside (on the step) and one foot outside (on the ground). His hand reaches out in both directions, explicitly representing the anguished division of his loyalties between his two families.

This highly detailed, nuanced psychological drama is staged in a surprisingly small format. Seldom was Rembrandt’s etched line so intricately fine as here. The line work is, however, relatively open and fluid rather than tight and pedantic.

In 1637, the year that this plate was etched, a quarrel between Rembrandt and an otherwise unknown Portuguese Jewish painter by the name of Samuel d’Orta was brought before the Amsterdam authorities. D’Orta’s affidavit suggests something about the Jewish market for biblical art in seventeenth-century Amsterdam. D’Orta reports that Rembrandt had sold him the etched plate identifiable as “Abraham Casting Out Hagar and Ishmael,” and had agreed not to sell the two or three impressions he had reserved for his “own curiosity.” D’Orta suspected, however, that Rembrandt either had broken or would break their agreement by continuing to sell impressions from the plate. Because artists normally retained their plates to publish further impressions or to control the number of prints circulating, the transaction was somewhat exceptional, and nothing is known of the outcome of the dispute. It indicates, however, that a Sephardic artist sought to invest in the sale of Rembrandt’s prints. Quite plausibly, d’Orta’s market would have included members of his Sephardic community. As early as 1637, then, Rembrandt’s biblical prints may have attracted buyers among the Portuguese Jews of Amsterdam.