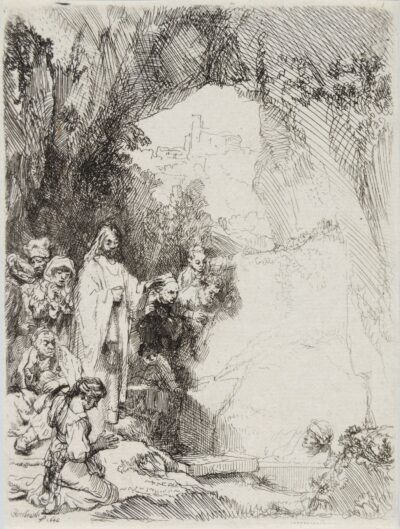

The Holy Family

Rembrandt Van Rijn

The Holy Family

etching

c. 1632

An original Rembrandt Van Rijn etching.

c. 1632

Original etching printed in black ink on laid paper.

Signed in the plate with the artist’s monogram lower right RHL.

A superb 17th century/lifetime impression of Bartsch and New Hollstein’s only state, Usticke’s first state of two, of this rare etching (characterized by G.W. Nowell-Usticke in his 1967 catalogue Rembrandt’s Etchings: States and Values as “a very scarce, attractive print,” and assigned his scarcity rating of “RR” [50-75 impressions extant in that year), showing the touch of burr on Joseph’s eye.

Catalog: Bartsch 62; Hind 95; Biorklund-Barnard 31-3; Usticke 62 i/ii; New Hollstein 114.

This intimate etching gives us a glimpse into the private lives of the Holy Family: the infant Jesus, Mary and Joseph. An interest in the domestic life of the Holy Family had a strong tradition in Netherlandish painting and printmaking from the fifteenth century onwards. This etching is so lacking in the traditional symbols of divinity such as haloes that one might mistake it for an ordinary scene of tranquile Dutch domestic life. Mary, seated on a low step, offers her breast to the child, who has apparently fallen peacefully asleep while nursing. She has a box of linens ready to hand at her side. Behind her at right, propped up on end with a shawl over it, is a wicker bakermat, a legless basketry couch used in seventeenth-century Holland by nursing mothers. In the left background one sees Joseph, seated in profile reading, presumably from a sacred text. The relaxed domesticity of the scene is best represented by the slipper that has casually dropped from Mary’s foot.

The background of the featureless interior is enveloped in a transparent web of shifting shadow, while Rembrandt uses areas of blank white paper to focus light on Mary and the child. The delicate play of light and shadow over Mary’s features subtly heightens her musing, reflective expression. One can choose to view her as simply a mother who has fallen into a dreamy trance while nursing her child, or as the mother of the Savior meditating on this particular child’s special destiny.

This monogrammed but undated etching, typical of Rembrandt’s 1630s etchings in its wiry calligraphic line such as “The Pancake Woman” of 1635 (Bartsch 124). It is, however, usually dated about 1632, the last year in which Rembrandt is known to have used the RHL monogram seen in it.