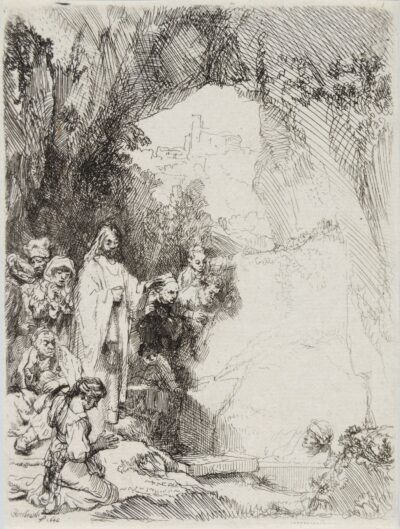

Virgin and Child in the Clouds

Rembrandt Van Rijn

Virgin and Child in the Clouds

etching & drypoint

1641

An original Rembrandt Van Rijn etching & drypoint print.

1641

Original etching and drypoint printed in black ink on laid paper bearing a portion of a Strasbourg Lily watermark (Ash/Fletcher 36).

Signed and dated in the plate in the shadows lower center Rembrandt f. / 1641.

A fine 17th century impression of Bartsch’s only state, Usticke and New Hollstein’s second and final state (characterized by G.W. Nowell-Usticke in his 1967 catalogue Rembrandt’s Etchings: States and Values, as “a rather uncommon print”), printed after the addition of the two dots in the upper right corner.

Catalog: Bartsch 61; Hind 186; Biorklund-Barnard 41-H; Usticke 61 ii/ii; New Hollstein 188 ii/ii.

6 5/8 x 4 3/16 inches

Sheet Size: 6 11/16 x 4 3/16 inches

Rembrandt made a false start when he embarked on this print, and an upside-down face is visible at Mary’s left knee. Evidently the artist soon realized that the head was too small and poorly positioned in the picture plane. Without erasing the traces of his initial design he turned the plate 180 degrees and started afresh.

Rembrandt may have drawn inspiration for the print from several sources, including Dürer’s “Madonna on the Crescent Moon” from the title page of his Life of the Virgin, a small print of the same subject by Jan van de Velde after a design by Willem Buytewech, and Federico Barocci’s “Madonna and Child,” all of which have been suggested. On closer inspection, it would not be an overstatement to describe Rembrandt’s print as a free copy after Barocci. The two are nearly the same size, and Rembrandt’s seated Virgin Mary is almost an exact repetition of them Italian master’s (albeit in reverse). It is striking that Rembrandt faithfully adopted the uncommon motif of the Virgin Mary’s folded hands. He also appears to have followed Barocci in the distribution of light and dark, and in the etching technique – with simple cross-hatching in the shaded areas. Nevertheless, the two prints are very different in tone: Barocci’s Madonna is a young, sweetly smiling girl with an idealized, symmetrical doll’s face. The Christ child is a burly infant that gazes directly at the viewer and makes a gesture of blessing. In contrast, Rembrandt’s Virgin seems scarcely aware of the child’s presence. She stares past the viewer into the distance. His Christ is also less robust, a sickly baby that turns away from the viewer, wholly unconscious of his divinity. When set beside Barocci’s sprightly counter-reformation icon, Rembrandt’s Madonna seems laden with unfathomable emotional ambiguity. It is safe to assume that Rembrandt owned an impression of Barocci’s etching, as his 1656 inventory lists a ‘Ditto [book] with copper prints by Vanni and others including Barocci’.