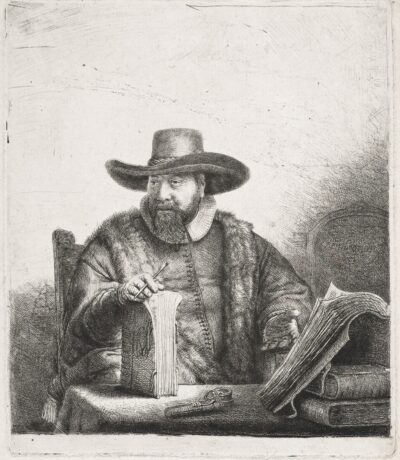

The Rat Catcher (The rat-poison peddler)

Rembrandt Van Rijn

The Rat Catcher (The rat-poison peddler)

etching

1632

An original Rembrandt Van Rijn etching.

1632

Original etching printed in black ink on laid paper bearing the “Double Headed Eagle” watermark (Ash/Fletcher 15).

Signed with the artist’s monogram and dated in the plate lower right RHL 1632 (the last two numerals are reversed).

A superb 17th century/lifetime impression of Bartsch and New Hollstein’s third and final state, Usticke’s first state of two, of this rare etching (characterized by G.W. Nowell-Usticke in his 1967 catalogue Rembrandt’s Etchings: States and Values as “a scarce plate,” and assigned his scarcity rating of “R” [75-125 impressions extant in that year]), printed after the addition of the parallel diagonal shading to the foliage behind the head of the rat catcher but before the strengthening of the outline of the back of his hat, the slipt stroke through his right foot printing strongly and the distant cottages to the right clear, showing no signs of wear.

Catalog: Bartsch 121 iii/iii, Hind 97, Biorklund-Barnard 32-C, Usticke 121 i/ii; New Hollstein 111 iii/iii.

Vagabonds, beggars, and street people in Rembrandt’s time often justified their existence and their requests for money by plying a minor trade or by providing musical entertainment, selling quack medical potions and poisons to control household vermin. “The Rat Catcher” (or “Rat Poison Peddler”) of 1632 is one of Rembrandt’s furthest excursions into the realm of the picturesque, the caricatural and the grotesque. It is a veritable essay on the pleasures of picturesque dilapidation: everything is frayed, broken, shaggy or distinctly irregular in profile. Rembrandt makes use of staged biting of the etched lines in order to achieve a sense of deep atmospheric recession. The pale image of the thatched cottage in the distance echoes the more firmly delineated cottage in the foreground where the rat-poison peddler is attempting to make his sale. The rat catcher is a wonderfully grotesque figure, not only in his irregular silhouette but also in the lovingly described details of his costume and equipment. He holds a pole surmounted by a cage from the top of which a live rat peers down at the potential customer. The corpses of other rats hang by their necks from the cage, testimony to the rat exterminator’s effectiveness. Another live rat, sleek and seemingly well-fed, rides on the rat catcher’s shoulder like a pet parrot. The rat catcher has a shaggy fur cloak flung over his other shoulder and an elaborate sword or knife – a theatrical advertisement of his killing prowess? – hangs from a sash. He offers a packet of ratsbane (red arsenic) to the prospective customer, while his dwarfish assistant, who looks expectantly up at the potential customer, holds a box with a sliding lid that presumably contains further packets of poison. The client decisively pushes away the rat catcher’s hand with the back of his own while looking away, perhaps overpowered by the reek of the peddler’s victims and the rat catcher himself. In the middle distance prowls – a kind of footnote to the scene in the foreground – a scrawny cat, enemy of rats.

The Rat Catcher is the first etching in which Rembrandt works the studies of old beggars that had been preoccupying him for years into a full-scale genre scene.