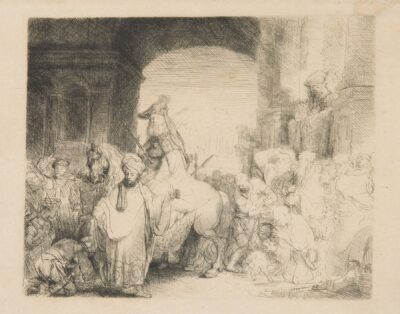

The Raising of Lazarus. Small Plate

Rembrandt Van Rijn

The Raising of Lazarus. Small Plate

etching

1642

An original Rembrandt Van Rijn etching.

1642

Original etching printed in black ink on laid paper

Signed and dated in the plate lower left Rembrandt f. 1642.

A fine late 18th century impression (possibly by Claude Henry Watelet) of Bartsch and New Hollstein’s second and final state, Usticke’s, second state of three, printed after the addition of the diagonal shading to the forehead of Lazarus, but well before the very late rebiting of the plate.

Catalog: Bartsch 72 ii/ii; Hind 198; Biorklund-Barnard 42-B; Usticke 72 ii/iii; New Hollstein 206 ii/ii.

In the evangelist John’s account of Jesus’ miraculous raising of his friend Lazarus from the dead (John 11:1-44), Christ explains to Lazarus’s sister, Martha, the broader significance of the miracle before he performs it: through belief in him, the son of God, one shall achieve salvation and eternal life. He says, “I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live,” and, “whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die.” John tells us that Jesus loved Mary, Martha, and their brother Lazarus, followers of Christ residing in Bethany near Jerusalem, and that he wept for Lazarus. Christ’s resurrection of Lazarus from the dead was one of his most dramatic miracles and we are told that many witnesses to the event were converted to belief in him. It was also one of Jesus’ public acts that most seriously alarmed the reigning religious authorities and led to Christ’s subsequent arrest, trial and crucifixion.

Rembrandt had illustrated the miracle in a painting of about 1630-31 and in a related large, highly finished etching (Bartsch 73), which he had labored over and taken through many states. Both of these interpretations of the story involved a dark cavelike tomb and highly melodramatic gestures, with Christ’s arm raised in command as he cries out “Lazarus, come forth.” Rembrandt’s conception in this small etching of 1642 is much simpler. He locates the miracle out of doors in a landscape flooded with daylight. John’s text tells us regarding the grave only that “It was a cave, and a stone lay upon it.” Here the stone slab has been moved aside. Rembrandt’s understated 1642 interpretation of the subject seems to suggest that for Christ all things are simple, that a miracle is just another everyday event. Christ’s gestures and those of the spectators, Mary and Martha and their comforters, are extremely restrained. Lazarus opens his eyes and his mouth gapes with surprise, a wholly different effect than the eerie corpse magnetically drawn upward by Christ’s gesture in the earlier painting and print.

The emphasis on landscape, albeit highly imaginary and grottolike, is not surprising because Rembrandt’s first dated landscape prints had been etched in the previous year, 1641. The blank white paper of the large rockface behind the diminutive figure of the resurrected man effectively suggests Lazarus’s return to the radiant light of day and enables us to better focus on his head and shoulders still wrapped in their grave clothes.