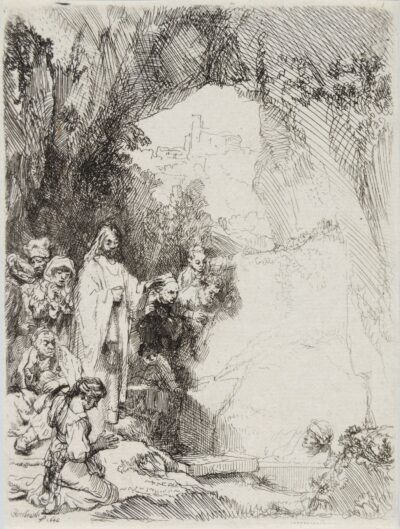

Portrait of a Boy in Profile

Rembrandt Van Rijn

Portrait of a Boy in Profile

etching

1641

An original Rembrandt Van Rijn etching.

1641

Original etching printed in black ink on laid paper

Signed and dated in the plate upper center Rembrandt f 164(1).

A superb 17th century/lifetime impression of Bartsch’s only state, Usticke’s first state, New Hollstein’s second and final state of this rare etching (characterized by G.W. Nowell-sticke in his 1967 catalogue Rembrandt’s Etchings: States and Values as “a very attractive little portrait . . .”, and assigned his scarcity rating of “RR+” [50-75 impressions extant in that year]), printed after the grain and craquelure in the background was largely burnished out.

Catalog: Bartsch 310; Hind 188; Biorklund-Barnard 41-K; Usticke 310 i/i; New Hollstein 195 ii/ii.

It is still not certain who this little boy is. In 1859 Blanc identified him as the young William II of Orange (1625-50). The author based this on a painting which was thought to be of the prince with his tutor Jacob Cats but this later turned out to be incorrect. Almost one hundred years later George Biörklund came to the same conclusion, but then on the basis of a portrait of the prince at the age of nine engraved by Willem Delff in 1635. In 1905, subsequently supported by De Bruijn, Valentiner suggested that it could be Rembrandt’s son Rombertus, who was born in 1645, but we now know that the child died when he was just two months old. Hofstede de Groot came up with the more likely suggestion that it could be ‘schipper Gerbrants soontjen’ (shipmaster Gerbrant’s son), mentioned in Clement de Jonghe’s inventory of 1679.

In the execution of the portrait it is noticeable that the child’s torso, the collar and the sleeve have been indicated in detail, but the chest and stomach have been shaded with brisk, almost careless zigzag lines. The face on the other hand is fine and very meticulously lit. All the same Rembrandt will have been disappointed when the etched plate came out of the acid bath. The etching ground proved not only to have been porous but had cracked too, and as a result the earliest impressions have irregular heavy grain and extensive craquelure all over the image. He may have overheated the copper plate when he applied the etching ground. Rembrandt burnished out most of the grain and craque3lure from the plate in the background and in the blank areas of the boy’s face, but elsewhere he was unable to do this without also removing the image itself.